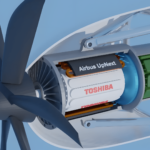

Airbus and Toshiba are joining forces to develop a superconducting aircraft engine. The technology uses liquid hydrogen as fuel and to cool the propulsion system, which promises greater efficiency. airbus

The aviation industry is faced with the challenge of drastically reducing its emissions. Airbus and Toshiba have now teamed up to develop a promising solution: a superconducting engine for hydrogen-powered aircraft. The concept is based on the use of liquid hydrogen, which is cooled to extremely low temperatures of -253 degrees Celsius.

At these temperatures, certain materials become superconducting, meaning they can conduct electric current with almost no resistance. This enables the construction of significantly lighter and more efficient electric motors for aircraft.

airbus announced in a statement that the liquid hydrogen will not only serve as fuel, but will also be used to cool the electric drive system. According to the aviation group, this cryogenic technology could enable almost loss-free power transfer within the aircraft’s electrical systems, significantly improving energy efficiency and performance. Airbus and Toshiba show how the new engine works.

Airbus has been testing superconducting technologies for a decade and recently unveiled a demonstrator for a two-megawatt superconducting electric propulsion system. Toshiba, on the other hand, has been researching applications for superconductivity for almost 50 years and in June 2022 presented the prototype of a superconducting motor in the two-megawatt class for mobility applications.

However, the development of superconducting engines for aviation also brings with it special challenges, and these could represent major hurdles in practice. The infrastructure at airports would have to be adapted to store and handle liquid hydrogen at extremely low temperatures. In addition, the pipes and pumps are very special for such low temperatures and often only have a limited service life.

Superconductivity was discovered in 1911 by the Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, who even received the Nobel Prize in 1913 for his research. Since then, the technology has found applications in everything from magnetic levitation trains to particle accelerators. Its application in aviation could now mark another milestone in the history of this technology – if it can be put into practice.